How to Build a Design System Teams Actually Use

Most design systems die the same way. Someone spends months building a polished component library, writes thorough documentation, presents it at an all-hands, and six months later, three teams are still building buttons from scratch. The component library sits in Figma like a museum exhibit: impressive, untouched.

The build isn’t the hard part. Adoption is. And the gap between the two is where most how-to guides stop short. They’ll walk you through tokens, components, and documentation, then leave you with a system nobody opens.

This guide covers the full arc: how to build a design system that your team actually picks up, extends, and keeps running without you. Because a design system that doesn’t get used is just a style guide with better branding.

What Goes Into a Design System (And What to Leave Out)

A design system is a collection of reusable components, design tokens, patterns, and usage guidelines that teams use to build consistent products faster. It’s not a style guide (too static), not a UI kit (too shallow), and not a Figma file with 400 components nobody asked for.

Here’s the difference:

[COMPARISON TABLE: Design System vs. Style Guide vs. Component Library]

| Design System | Style Guide | Component Library | |

| What it contains | Tokens, components, patterns, documentation, governance model | Colors, fonts, logo usage, brand rules | Pre-built UI components (buttons, modals, inputs) |

| Who uses it | Designers, engineers, product managers | Brand and marketing teams | Designers and front-end engineers |

| How it’s maintained | Living — updated with the product | Static — updated periodically | Semi-living — updated when components change |

| Code included? | Yes — design and code stay in sync | No | Sometimes |

| Teaches teams how to build? | Yes — with patterns and guidelines | No — just what it should look like | Partially — shows what to use, not when or why |

| Scales across products? | Yes | Loosely | Yes, if well-organized |

| Governance built in? | Yes — contribution model, versioning | No | Rarely |

The over-scoping trap is real. We’ve seen teams try to document every edge case before shipping a single component. That’s backwards. Start with the 20% of components that cover 80% of your product surface: buttons, form inputs, cards, navigation, typography. Ship those. Let usage patterns tell you what to build next.

A right-sized design system serves the team using it today. Not a hypothetical future team building a hypothetical future product.

How to Audit Your UI Before Building Anything

Before you build a single token, screenshot your product. All of it. Every screen, every state, every platform. Then spread it out and look for the mess.

You’re looking for three things:

Inconsistencies — the same button in four different shades of blue. A card component with three different border radii depending on who built it. Form labels that are 14px on one page and 16px on another. These are your highest-value fixes.

Duplication — components your engineers already built but your designers don’t know about. Or components in your Figma libraries that were never implemented in code. The gap between design files and production code is often the biggest source of waste in a product team’s workflow.

Patterns — recurring layouts, interaction models, or content structures that appear across multiple features. These are your future pattern library.

[VISUAL PLACEHOLDER: UI audit checklist infographic — showing the three categories (inconsistencies, duplication, patterns) with example screenshots]

Here’s what catches most teams off guard: the audit isn’t just a design exercise. Your engineers need to be in the room. They’ve likely built reusable components that aren’t documented anywhere in Figma. They know which CSS variables are already standardized and which ones are a free-for-all. Skipping the engineering audit means you’ll build a design system that creates a parallel universe instead of consolidating the one you already have.

Organize your findings into categories: color, typography, spacing, components, patterns. Then prioritize by frequency and inconsistency. The components that appear on every screen and look different every time? Those are your first sprint.

The Build Sequence: Tokens, Components, Patterns

The build follows a clear sequence, and skipping steps creates debt you’ll pay later.

Phase 1: Design Tokens (Week 1–2) Tokens are the atomic decisions: color values, type scales, spacing units, border radii, elevation shadows. Think of them as the vocabulary your system speaks. Define a token set for color (brand, semantic, and neutral), typography (a type scale with 5–7 sizes), and spacing (typically an 8px grid with 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, 48 increments).

The key here: tokens aren’t decorative. They’re functional. A semantic color token like color-action-primary is more useful than blue-500 because it carries intent. When your brand refreshes, you change one token — not 400 components.

Phase 2: Core Components (Week 2–5) Start small. Buttons, inputs, selects, checkboxes, toggles, cards, modals, tooltips. Brad Frost’s atomic design model is still the clearest framework here: build atoms (individual elements), combine them into molecules (a search bar is an input + button + icon), then assemble organisms (a full header with nav, search, and user menu).

Each component needs three things: a design spec in Figma, a coded implementation that mirrors it, and usage documentation that explains when to use it and when not to.

Phase 3: Patterns and Templates (Week 5–8) Patterns are the recipes. A form pattern dictates how labels, inputs, validation, and submit actions work together. A data table pattern covers sorting, filtering, pagination, and empty states. A settings page template shows how multiple patterns compose into a full screen.

This is where design systems graduate from “component collection” to “product accelerator.”

[VISUAL PLACEHOLDER: Build sequence timeline — showing Phases 1-3 with team pairing overlay, indicating where product team members join at each phase]

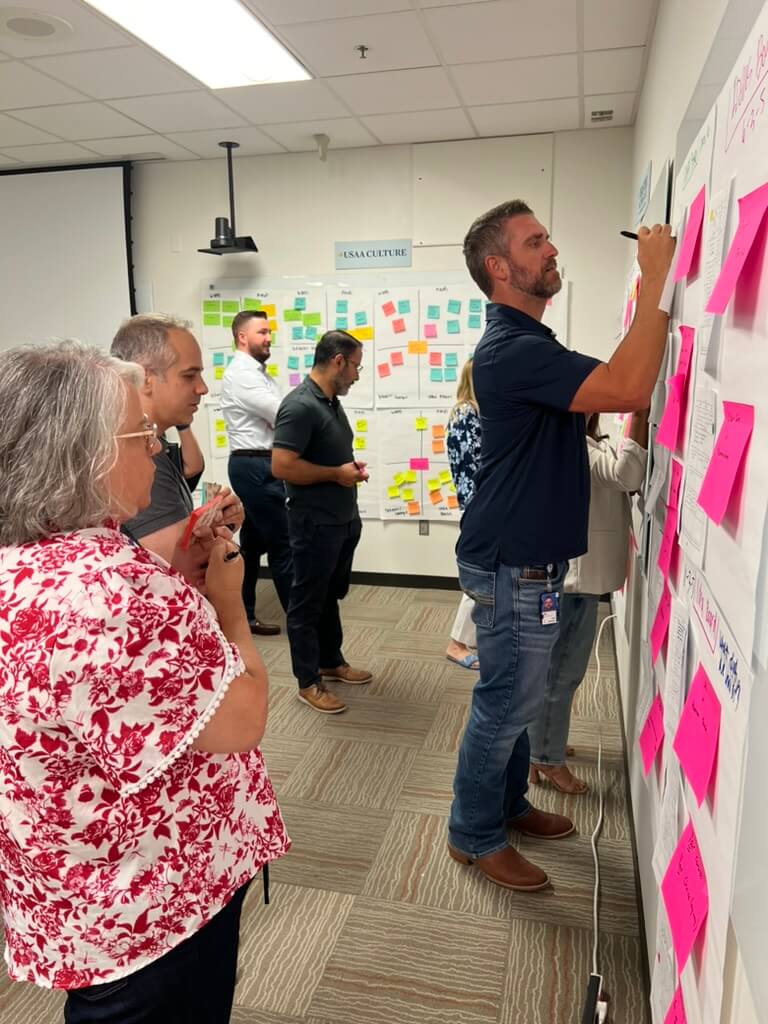

The piece most guides skip: build with your product teams, not for them. Your engineers should pair with the system builders from Phase 2 onward. Your product designers should join component reviews. Not as reviewers — as co-builders. By the time the system ships, the people who need to use it have already built parts of it. They know where things live. They know the naming conventions. They have muscle memory.

This is the difference between a design system your team receives and a design system your team owns. That shift, from handoff to capability transfer, is what determines whether the system gets used six months from launch.

Why Most Design Systems Fail After Launch

The failure pattern is consistent enough to name it: the design system gets built by a dedicated team (or a single passionate designer), shipped with good intentions, and slowly abandoned because nobody else feels ownership over it.

Three things kill adoption:

No involvement during the build. If your product teams first see the design system at a demo, you’ve already lost. They’ll view it as something imposed on them, another tool to learn, another constraint. The teams that adopt fastest are the ones who contributed components. They’re not learning a new system. They’re using one they helped create.

No governance model. Who approves new components? How do teams request changes? What happens when someone needs a variant that doesn’t exist? Without answers, teams route around the system. They fork components. They build custom. Within a quarter, you’ve got a design system and three shadow systems.

No adoption metrics. If you can’t measure whether teams are using the system, you can’t improve it. And leadership can’t justify continued investment in something that has no visible impact. Here’s the distinction most teams miss: there’s a difference between component usage (how often a button gets used) and component coverage (what percentage of your UI is actually built with system components). A team might use your button everywhere but build everything else custom. That’s 10% coverage with the illusion of adoption. Figma’s 2025 State of Design Systems report found that adoption stalls at 60–70% in mid-tier organizations, often because teams lack the governance and metrics to push past early wins.

The uncomfortable truth: building the design system is the straightforward part. Getting 5, 10, 50 people to change how they work? That’s the real project.

How to Measure Design System Adoption {#how-to-measure-adoption}

You need four metrics. Track them monthly.

Component coverage rate. What percentage of your product UI is built with design system components versus custom code? This is the metric that matters most. Industry benchmarks suggest targeting 80%+ for mature systems. If you’re sitting at 40%, you’re spending engineering time rebuilding what already exists.

Detachment rate. How often do teams override or detach from system components? High detachment means the system isn’t flexible enough, or teams don’t trust it. Track which components get overridden most and fix the gaps.

Contribution rate. Are teams submitting new components, variants, or bug fixes back to the system? A healthy design system has contributions from outside the core team. Zero contributions means the system is a one-way street, and one-way streets eventually hit dead ends.

Time-to-build. How long does it take to build a new screen or feature with the system versus without it? This is your ROI metric. If your design system isn’t making teams faster, something is broken, either in the system or in how teams are trained to use it.

Set up a simple dashboard that tracks these four numbers. Review it monthly with your design ops lead or whoever governs the system. The dashboard isn’t just for measurement. It’s the artifact that keeps leadership invested and teams accountable.

Extending the System After the Builders Leave

Every design system faces this moment: the person (or team) who built it moves on. New priorities absorb their time. Or the engagement with the external team that built it wraps up. What happens next determines whether the system thrives or decays.

Three things need to be in place before that moment arrives:

A contribution model. Document how teams add new components, propose changes, and report issues. Make it lightweight: a contribution template, a Slack channel, and a monthly review cadence. If contributing feels harder than building custom, teams will build custom.

A governance owner. Someone, even if it’s a rotating role, needs to own the system’s health. They review contributions, flag inconsistencies, update documentation, and run the monthly metrics review. This doesn’t need to be a full-time role. But it needs to be someone’s named responsibility.

A playbook your team can actually follow. Not a 200-page wiki nobody reads. A concise playbook that covers how to find components, how to use tokens, how to request new patterns, and how to contribute back. The playbook is the design system’s user manual, and like any good product, it should be usable without a training session.

The result: by quarter end, your team extends the system without the people who originally built it. New designers pick up the component library and start shipping on day one. Engineers reference the token system instead of hardcoding values. Product managers scope features knowing what’s already built.

That’s the goal. Not a perfect design system. A self-sustaining one.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to build a design system?

A right-sized design system (tokens, core components, basic documentation) can ship in 6–8 weeks for a focused team. The mistake is trying to build everything at once. Start with the 15–20 components that cover 80% of your UI, ship them, and iterate based on what teams actually need. Full maturity, including patterns, templates, and governance, typically takes 3–6 months.

Do small teams need a design system?

Yes, but a right-sized one. Even a team of three benefits from shared tokens and a handful of core components. You don’t need a 200-component library. You need enough shared language that two designers don’t accidentally ship two different button styles. Start small. A color palette, type scale, and five core components is a design system.

What tools are best for building a design system?

Figma is the current standard for design-side systems, with robust library and variable support. For code, it depends on your stack. Storybook is widely used for component documentation, and most teams build coded components in React, Vue, or web components. The tool matters less than the process: whatever you pick, design and code need to stay in sync through tokens and shared naming conventions.

A design system that teams actually use isn’t built with better components. It’s built with better process, the kind that pairs your team with the builders, transfers capability as it goes, and leaves behind a system people can extend on their own.

If your team is starting a design system, or rebuilding one that didn’t stick, that pairing model is where we’d start the conversation. The system ships. The playbook stays. Your team keeps it.

![Design System Governance That Survives Handoff [Framework]](https://cabinco.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/43dd6a6c1fac961f0536e949034691bc52ded48f-1400x2101.webp)

![Salesforce Implementation Checklist: Complete Guide [2026]](https://cabinco.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DSC09010-1400x933.jpg)

![Design Token Examples That Actually Scale [With Code]](https://cabinco.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Cabin_Nov25-3-1400x933.jpg)

![Component Library Examples Teams Actually Use [With Breakdowns]](https://cabinco.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/DSC08958-1400x933.jpg)

![Consultant Exit Strategy That Actually Works [With Timeline]](https://cabinco.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/2E7CFF24-FC73-4F12-ADB0-E012D0426CF4_1_105_c.jpeg)